There is increasing research surrounding the importance of metacognition; Ofsted itself is encouraging schools to support pupils’ memory and cognition to enable them to ‘learn more and remember more’. However, the research is not as wide-ranging for those students with special educational needs and disabilities and it is somewhat harder to pin down how the pedagogy of cognition can be applied to support their learning.

Metacognition refers to cognitions about regulating our own mental states (Flavel, 1949). We typically consider metacognition to be ‘thinking about thinking’. Flavel identified a taxonomy which distinguished between “metacognitive knowledge” (an individual’s beliefs and knowledge about cognitions, including declarative knowledge, procedural knowledge, and knowledge about strategy use) and “metacognitive skills” (an individual’s ability to assess and control their own cognitive processes). Metacognition is considered essential for day-to-day behavioural functioning because it is this monitoring of one’s internal states that allows one to self-regulate (Nelson & Leonesio, 1988). The EEF (2020) captures metacognition as a cycle of planning, monitoring and evaluating.

Research shows that learners with SEND can be less proficient at self-regulation, may be less likely to develop independence with learning strategies, and may need support to reach deeper levels of metacognitive thinking than their non-SEND peers (Porter, 2002). Studies suggest that for some SEND categories such as ASD, there may be a significant diminished accuracy in their judgments of confidence and metacognitive accuracy, indicating metacognitive monitoring impairments in ASD compared to neurotypical young people. Furthermore, for some children with ASD, they may also demonstrate socio-communicative difficulties as well as potentially being slower to recognise emotions and calibrate confidence accuracy – all of these feature within metacognition. However, benefits of supporting SEND learners to develop metacognition is well supported:

“Pupils whose special educational needs affect their ability to organise information, stay focused on task, or comprehend information in context may benefit from metacognitive skills training that explicitly shows them how to look for the bigger picture, and how to prompt or cue themselves to monitor their progress.” (SESS, 2019)

TT Education is currently working with Special Schools to explore how children with special educational needs such as ASD and SEMH can develop metacognition, help them to access the curriculum and also support their performance across personal, social, emotional and academic areas. Some of the aims of the work include promoting the use of metacognitive strategies to enable learners to be more independent in monitoring their own learning, be able to problem-solve and reason, have an increased positive attitude, and support their memory and recall.

Underpinned by TT Education’s Path to Success model, and taking account of research on metacognition, teaching, learning and SEND, we have been working with SEND learners and Special School staff to understand strategies that can support metacognition.

Ways to support SEND learners to foster metacognition through the Path to Success include:

Experience it:

Pupils develop an understanding of the world through rich, active and meaningful learning experiences outside the classroom. This may vary for SEND learners depending on their needs, but could include opportunities to communicate about likes and dislikes, or use senses to explore outdoor spaces such as gardens and wooded areas. Ensuring learners can use prior knowledge to support learning is another important aspect of metacognition: this might be done by checking what learners already know through TT Education strategies like the graffiti wall, 60 seconds and graphic organisers, and pre-teaching key content such as vocabulary.

Play with it:

An example to support playing with metacognitive strategies can include opportunities for rehearsal, review and retrieval of learning, which can include visual representations. Repetition is also important, with regular opportunities for learners to experience and play with the learning to help processing and memory. Exposing learners to texts and providing opportunities to respond to known, repetitive language patterns are also examples. For those who struggle with processing, ‘play with it’ encourages short burst-practice by turning learning into games – ‘gamification’. Gamification of learning can also remove some of the fear and anxiety that can come with new learning.

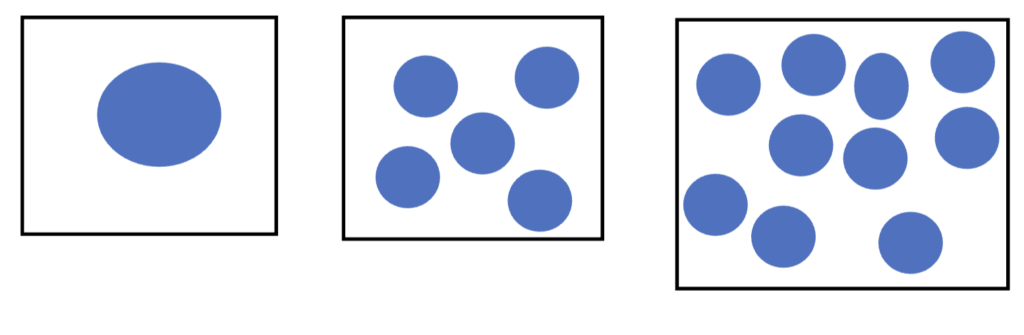

Encouraging children to develop personalised self-regulation and self-awareness strategies can also be a way to support students with SEND. This can involve visual representations to make associations and then develop this to apply to numerical systems (this could be supported by using manipulatives, as well as visuals).

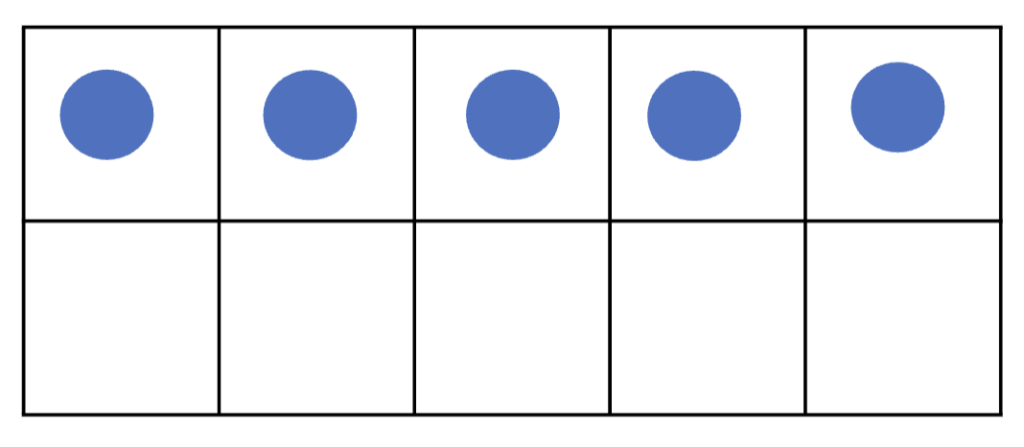

Learners familiar with ‘tens frames’ can use these as visuals instead.

This can then be extended from 1 to 10, as learners become more comfortable and confident and include wider visuals. Scaffolding multiple modalities also reinforces children having greater access to ‘experience it’.

Use it:

Learners can begin to plan, monitor and evaluate their learning, enabling them to understand where and how they can make changes to their learning, to be more successful. This can include using assisted technology and personalised communication methods. Metacognitive thinking can also be supported by considering the scaffolds used – maybe writing frames, knowledge organisers or structure strips. Learners can also use metacognitive strategies through the use of prompt sheets, checklists and the structuring of learning into short ‘chunks’ (EEF, 2020).

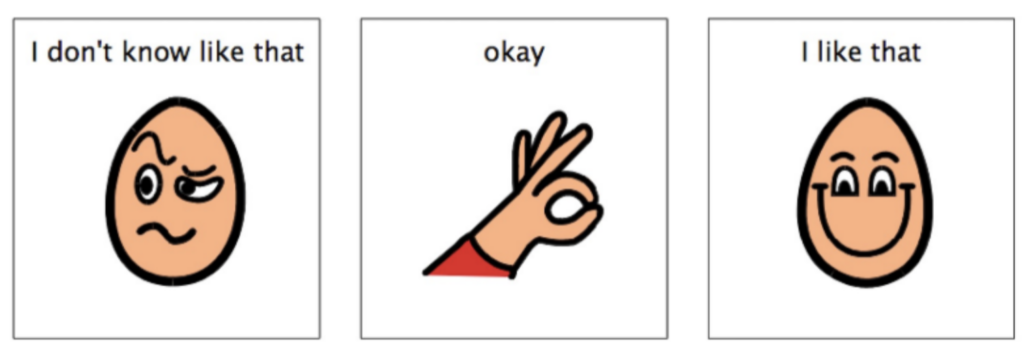

Teachers can ensure that they give time for reflective thinking and use multi-sensory approaches with SEND learners such as whether they like, dislike or have no preference, for instance with different types of flower based on smell, or food items being made as part of food technology or PSHE, different books, different paint brushes, and so on.

Develop it:

Allow time for children to explain their understanding, or consider how they can use reflection to further their own personal development. Using adaptive and assistive technology, visuals and prompts to support learners’ needs can aid opportunities for learners to ‘think about thinking and learning’.

Connect it:

In the connect it stage learners make links, for example memory links which show they may have seen or experienced something before. This can be done by responding with a facial cue, body posture or vocal pattern, to show they like or dislike something. Learners could use the pictorial prompts or other representations to show their thinking, like the ones shown earlier.